A new Approach to Physical Education

by: Alessandra Fazioa, Emanuele Isidoria , Óscar Chiva Bartoll

CLIL method is based on the reconstruction of the subject according to four basic aspects which facilitate the work and development of linguistic competence (content, communication, culture and cognition, the so-called “4Cs”), in PE, these four points can be used to enhance the critical aspect of the teaching-learning process.

«Content» refers to the selection and handling of the subject content. In accordance with Fernández-Balboa and Sicilia (2005), for PE we suggest the selection of contents that highlight social and intellectual aspects. This would replace the too technical Anglo-Saxon approach which has gradually been implemented in PE.

As regards «communication», we suggest increasing STT (Student Talking Time) at the expense of TTT (Teacher Talking Time). This measure, applied to the «language of learning», the «language for learning» and the «learning through language» contributes positively to the successful implementation of CLIL (Coral, 2012: 30). It also helps optimize learning in an active and participatory way.

The «culture» aspect provides an excellent opportunity for discussing the practical content of the subject, especially when it comes to ideological preconceptions and myths related to PE and sport. Thus, through a rational process of deconstruction of contents that have been accepted in an uncritical way, students will be ready to form their own independent opinions about each content. In this way they will be able to integrate and connect their acquired knowledge with the real world.

Finally, we must consider the aspect of «cognition», rooted in the cognitive domain of Bloom’s taxonomy (1956), or even more specifically in the review published by Anderson & Krathwohl (2000), which proposes the following continuum of skills and thought processes involved in learning tasks: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate and create. CLIL methodology requires high levels of cognitive involvement in which cognitive activities of analysis, evaluation and creation are put into practice.

Four steps should be clearly held in mind when redesigning the teaching-learning process, as can be seen in the following concept of CLIL based on Critical Pedagogy:

- «What»: selection of content and objectives.

- «When»: sequencing the contents.

- «How»: choice of methodological strategies and teaching styles.

- «What, how and when to assess».

The 4Cs framework fits perfectly with the objectives, content and evaluation criteria for a PE model based on critical pedagogy. Below, we suggest how these elements can be used to integrate CLIL and Critical Pedagogy.

Learning objectives and assessment criteria

The definition of educational objectives is one of the most difficult tasks for teachers. Rather than teaching by objectives so that PE becomes a mere tool, the correct approach according to López-Pastor (2002) and Rodríguez Rojo (1997) should concentrate on purpose, values and actions.

As seen in the previous sections, Critical Pedagogy focuses on the emancipatory interests of knowledge from a critical point of view (Habermas, 1982). Here we focus on clarifying the specific teaching/learning objectives that teachers must take into account when designing their CLIL syllabus based on critical pedagogy.

Many taxonomies have been applied to PE objectives (Simpson, 1966; Harrow, 1972; Castañer & Camerino, 1991). To achieve the requirements of CLIL using a critical pedagogy approach, we suggest organising learning objectives that take into account both the cognitive domain and psychomotor skills. In both cases they should follow an ordered sequence in terms of complexity and increased autonomy in the implementation of the tasks. Therefore, we opt for a number of objectives that, in relation to each of the selected contents, takes into account the following phases: perceiving and becoming familiar with the content, creating basic patterns, adapting and modifying the patterns to contextual needs, optimizing the decision-making-process and finally creating new responses on the basis of a critical and independent analysis of the acquired knowledge.

Given the open and flexible nature of the learning goals, the assessment criteria must be carefully correlated. Furthermore, the emancipatory approach should be followed, since in most PE tasks there can be several valid ways of achieving the same goal.

Review of contents

Educational contents are defined as the set of cultural forms and knowledge selected to make up a subject. In PE, cultural manifestations evolve over time, so a new analysis of contents must be made periodically (Contreras, 1998).

We must not forget that PE is made up of both scientific and social elements that should be given equal importance. As the desire to turn PE into a scientific discipline has prevailed, its humanistic contents have been left aside in order to promote a more scientific and technical profile.

It is our belief that the social and humanistic aspects of PE need to be reestablished by means of Critical Pedagogy. Some examples of how this can be achieved are illustrated in Table 1.

Methodological Approach

The methodology we propose for implementing CLIL in conjunction with critical pedagogy in PE must incorporate a teaching style that encourages student participation and, above all, develops the 4Cs framework.

Among the numerous trends and methodologies for teaching PE, Mosston & Ashworth (1999) have to be mentioned. Their book ‘Teaching Physical Education’ suggest a number of teaching styles that represent a continuum in the evolutionary process of teaching guiding students towards autonomy and creativity. Out of the eight styles they propose, those that best fit CLIL and Critical Pedagogy are those that elicit a state of cognitive dissonance in students:

- Guided Discovery

- Troubleshooting

- Creativity and autonomy.

All these styles provide a methodological option that establishes a clear relationship between PE and cognitive processes, favoring the emancipation of students and the development of their decision-making capacity.

All of them, in accordance with the requirements of both CLIL and Critical Pedagogy make use of processes and tasks such as: comparing, contrasting, planning, developing, classifying, hypothesizing, summarising, exploring, creating, inventing, reflecting etc.

Teaching Physical Education in English using CLIL Methodology: a Critical Perspective

By: Alessandra Fazioa, Emanuele Isidoria , Óscar Chiva Bartollb

Abstract

motivation” (2008).

The critical pedagogical perspective

An analysis of the scientific literature and specific cases of the use of CLIL with the English language to teach Physical Education (PE) indicates that the content of these cases seems to be very poor and centered on a purely practical rather than a deeper reflexive knowledge (Ruano, 2014). Moreover, this content seems to be selected in order to develop skills and abilities of a technical nature.This is due to the widespread conception of PE as an area of study and research whose main goal is simply to develop practical skills. Consequently, this subject is taught through technified methods focused on achieving goals related to the technical-tactical or bio-physiological aspects of sports and physical activity (Fernandez-Balboa, 1997).

If PE is taught in this way, that is to say, with little emphasis on the more profound contents of the subject, the development of critical thinking and interconnections with other disciplines on the curriculum, CLIL is unlikely to generate rich and deep learning. In such cases, CLIL courses tend to consist merely in a simple juxtaposition of some thematic blocks based on general topics of disciplines like anatomy (e.g. the skeleton and muscles), biology (e.g. health education) or techniques, rules, and tactics related to team sports and physical exercises (Coyle, Hood, Marsh, 2010).

An analysis of these contents reveals a lack of interconnection between PE, social sciences and the humanities (mainly history, sociology, philosophy, literature). This interconnection is fundamental in achieving the main goals of physical and sport education. If this connection does not occur, CLIL applied to PE does not generate authentic language and cultural learning, thereby contradicting one of the fundamental principles of CLIL, namely enhanced language learning in the context of improved reflexivity and communication aimed at developing pupils’ personality and their reflexive skills.

In brief, what is missing in CLIL applied to PE using the English language is a critical pedagogical perspective and a more critical approach with regard to its contents. An issue that should be analyzed critically for example is the one related to English as a lingua franca (ELF). That is to say, the one concerning the claim that English (as a lingua franca) acts as a means for promoting neo-capitalism in economic, cultural and globalized terms. In fact CLIL applied to PE will never become a critical pedagogical approach with regard to its relationship with its main learning language tool (Phillipson, 2008).

The main problem for CLIL applied to PE is that this methodology cannot be implemented if first we do not observe this field from the perspective of critical pedagogy. Such a critical perspective, however, is missing in both PE and CLIL as a methodology to teach language and culture (Marsh, 2013).

When we consider how CLIL is structured, we realize that by focusing only on the development of technical skills and competencies, this methodology cannot change our concept of PE towards a more social perspective, which is arguably one of the key objectives of CLIL since it aims at developing intercultural communication and mutual understanding among peoples and cultures.

However, we can help CLIL develop into a methodology for promoting change and social inclusion (by enhancing communication and language skills that help people become more aware of the world they live in) by means of physical education and sport. The concept of sport, when interpreted in a pedagogical perspective, that is as sport pedagogy, can sum up the concept of physical education (Haag, 1992). It is a universal concept that involves the body, the play/game duality, and movement. Both physical education and sport can contribute in a remarkable way to the richness and variety of using languages to promote knowledge, intercultural communication and mutual understanding.

Language Awaress in CLIL

“Language Awareness” (Hawkins, 1984) is currently defined by the Association for Language Awareness (ALA) as “explicit knowledge about language, conscious perception and sensitivity in language learning, language teaching and language use” (ALA, 2012). Language Awareness is a crucial approach aimed at changing language learners’ perspectives towards explicit understanding of how language is used in a variety of contexts. In Marsh’s words (2012), Language Awareness “[…] is directly linked to the shift from focus on ‘form’ to ‘meaning’ and links to how people best learn languages, and how they can achieve deeper understanding of how to use languages in communication. By giving attention to language patterns found in usage, critical thinking skills can also be developed thus enabling a student to develop knowledge”

This field of study is strictly linked to current theories and practices in language teaching such as code-switching using English as a Lingua Franca (Cogo, 2009) and conceptual vocabulary (Thordarottir, 2011). Language Awareness also plays a significant role in investigating communicative awareness (Garret and James, 2000), critical language awareness (Fairclough, 1992), corpus linguistics for exploring connections between language patterns and language use in context (Sinclair 2004, O’Keefe, McCarthy and Walsh 2007) and pragmatics (Ishihara, 2007).

Thus Language Awareness covers a wide spectrum of fields and a broad range of issues related to language learning and can be considered as an approach that stimulates reflexivity and sensitivity in language/language learning but that also gives learners the ability to explore language and/or the language learning process and to appreciate it.

Language Proficiency

Although we agree with Barbero’s (2011) idea about the extreme diversity between languages and disciplines and that such diversity has a strong impact on the application of the CLIL method, we strongly disagree with her definition of the language of PE. In fact in her definition she reduces and simplifies the language of PE to a context limited to practical functions/structures such as understanding and giving orders and instructions and this is the reason why she classifies the language of PE at an elementary level (as mentioned in Section1).The specific field of PE, the framework generally theorised by Barbero for CLIL methodology illustrated below in Fig. 1 can be applied to the field of PE.

According to Barbero (2011), the amount of language needed to communicate a given content is inversely proportional to the context. Consequently, greater proficiency is needed when communication is not related to a concrete situation and there are no additional indications other than those provided by the language itself. In this case, “Context-reduced communication […] relies primarily (or at the extreme of the continuum, exclusively) on linguistic cues to meaning, and thus successful interpretation of the message depends heavily on knowledge of the language itself (Cummins, 2000)”. The quantity of cognitive demand depends on both the cognitive content and the complexity of elaboration through mental processes.

Considering the quadrants of the diagram above, CLIL activities can be classified (2011) “in four categories resulting from the combination of their different language and content:

- low-demand of cognitive involvement that requires very limited use of the language;

- activities with low cognitive demand, focused on language;

- highdemand cognitive tasks that require limited use of the language;

- high-demand activity and cognitive linguistics” (Barbero, 2011)

Thus according to Cummins “Mastery of “academic” function in Quadrant 4 academic register) is a more formidable task because such uses require a high level of cognitive involvement and are only minimally supported by interpersonal and contextual cues. Under conditions of high cognitive demand, it is necessary for students to stretch their linguistic resources to the limit to function successfully. In short “the essential aspect of language proficiency is the ability to make complex meaning explicit in either oral or written modality by means of language itself rather than by means of contextual or paralinguistic cues (gesture, intonation etc.)” (Cummins, 2000: 69).

The CLIL challenge applied to PE consists in being able to follow the 4 quadrants in Barbero’s diagram (2011) as contextualised in the proposal in the next section and summarised in Table 1. In this way it would be possible to achieve a higher level of language proficiency when dealing with abstract concepts related to the lexicalization of movement not only in relationship to space and time, but also to body-part and to play/game duality.

Content and Language Integrated Learning CLIL

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) has become the umbrella term describing both learning another (content) subject such as physics or geography through the medium of a foreign language and learning a foreign language by studying a content-based subject.

Content and Language Integrated Learning – methodology article. In ELT, forms of CLIL have previously been known as «Content-based instruction», «English across the curriculum» and «Bilingual education».

- Why is CLIL important?

- How does CLIL work?

- The advantages of CLIL

- CLIL in the classroom

- The future of CLIL

- Where is CLIL happening?

1. Why is CLIL important?

With the expansion of the European Union, diversity of language and the need for communication are seen as central issues.

- Even with English as the main language, other languages are unlikely to disappear. Some countries have strong views regarding the use of other languages within their borders.

- With increased contact between countries, there will be an increase in the need for communicative skills in a second or third language.

- Languages will play a key role in curricula across Europe. Attention needs to be given to the training of teachers and the development of frameworks and methods which will improve the quality of language education.

-

The European Commission has been looking into the state of bilingualism and language education since the 1990s, and has a clear vision of a multilingual Europe in which people can function in two or three languages.

2. How does CLIL work?

The basis of CLIL is that content subjects are taught and learnt in a language which is not the mother tongue of the learners.

- Knowledge of the language becomes the means of learning content.

- Language is integrated into the broad curriculum.

- Learning is improved through increased motivation and the study of natural language seen in context. When learners are interested in a topic they are motivated to acquire language to communicate.

- CLIL is based on language acquisition rather than enforced learning.

- Language is seen in real-life situations in which students can acquire the language. This is natural language development which builds on other forms of learning.

- CLIL is long-term learning. Students become academically proficient in English after 5-7 years in a good bilingual programme.

- Fluency is more important than accuracy and errors are a natural part of language learning. Learners develop fluency in English by using English to communicate for a variety of purposes.

- Reading is the essential skill.

3. The advantages of CLIL

CLIL helps to:

- Introduce the wider cultural context

- Prepare for internationalisation

- Access International Certification and enhance the school profile

- Improve overall and specific language competence

- Prepare for future studies and / or working life

- Develop multilingual interests and attitudes

- Diversify methods & forms of classroom teaching and learning

- Increase learner motivation.

4. CLIL in the classroom

CLIL assumes that subject teachers are able to exploit opportunities for language learning. The best and most common opportunities arise through reading texts. CLIL draws on the lexical approach, encouraging learners to notice language while reading. Here is a paragraph from a text on fashion:

The treatment of this lexis has the following features:

- Noticing of the language by the learners

- Focus on lexis rather than grammar

- Focus on language related to the subject. Level and grading are unimportant

- Pre-, while- and post-reading tasks are as appropriate in the subject context as in the language context.

5. The future of CLIL

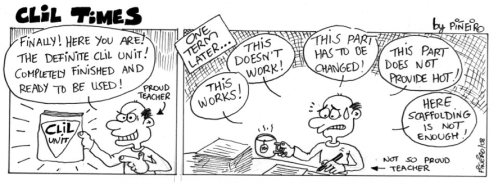

There is no doubt that learning a language and learning through a language are concurrent processes, but implementing CLIL requires a rethink of the traditional concepts of the language classroom and the language teacher. The immediate obstacles seem to be:

- Opposition to language teaching by subject teachers may come from language teachers themselves. Subject teachers may be unwilling to take on the responsibility.

- Most current CLIL programmes are experimental. There are few sound research-based empirical studies, while CLIL-type bilingual programmes are mainly seen to be marketable products in the private sector.

- CLIL is based on language acquisition, but in monolingual situations, a good deal of conscious learning is involved, demanding skills from the subject teacher.

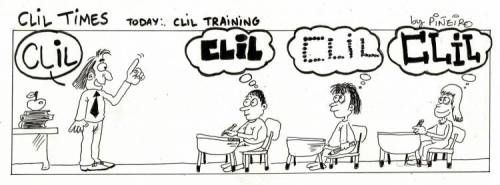

- The lack of CLIL teacher-training programmes suggests that the majority of teachers working on bilingual programmes may be ill-equipped to do the job adequately.

- There is little evidence to suggest that understanding of content is not reduced by lack of language competence. Current opinion seems to be that language ability can only be increased by content-based learning after a certain stage.

- Some aspects of CLIL are unnatural; such as the appreciation of the literature and culture of the learner’s own country through a second language.

Until CLIL training for teachers and materials issues are resolved, the immediate future remains with parallel rather than integrated content and language learning. However, the need for language teaching reform in the face of Europeanisation may make CLIL a common feature of many European education systems in the future.

6. Where is CLIL happening?

CLIL has precedents in immersion programmes (North America) and education through a minority or a national language (Spain, Wales, France), and many variations on education through a «foreign» language. Euro-funded projects show that CLIL or similar systems are being applied in some countries, but are not part of teacher-training programmes. There has been an increase in the number of schools offering ‘alternative’ bilingual curricula, and some research into training and methodology. Several major European organisations specialising in CLIL projects have emerged, including UNICOM, EuroCLIC and TIE-CLIL (see web references for details).

In the UK the incentive comes from the Content and Language Integration Project (CLIP) hosted by CILT, (the National Centre for Languages) which is the UK government’s centre of expertise on languages. CILT monitors a number of projects covering the 7-16 age range and involving innovations in language teaching such as the integration of French into the primary curriculum. Other research is based at the University of Nottingham, while teacher training and development courses in CLIL are available through NILE (the Norwich Institute for Language Education).